Research: Assessing the quality of hospitality services

Paper (1983) by: K. M. Haywood. Source: https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4319(83)90017-8.

I have read the paper so you don't have to. The 5 biggest lessons that teach you about the essence of hospitality, tourism and leisure management.

The term ‘quality’ while often used in marketing, is subject to some misunderstanding. One interpretation relates only to the properties and the physical and the performance characteristics of a hotel’s services. The second interpretation refers primarily to the value of the hotel as judged by the guest.

If the ultimate determinant of quality resides in a guest’s patronization of a hotel, quality is determined by want satisfaction. Quality, therefore, includes much more than the physical attributes of a ‘good’ hotel; its value is determined by a guest’s judgement and expectations. Guests make assessments of quality through patronization and by reacting to the hotel and the abilities of its employees to satisfy their wants.

Evaluating the quality [...] of services is complicated by the nature or characteristics of service.

We shall identify the major characteristics of these services and the resulting complications concerning consumer assessment of their quality.

- Intangibility; The core offerings of many services lack a physical form; they cannot be seen or touched for example. Consider such dimensions of service as care, hospitality, comfort, safety, security, information, advice. In choosing and evaluating the provision of these services it is common for guests to use tangible clues to judge quality. The intangibility of hospitality services makes them difficult to evaluate prior to use or patronage. Moreover, the fact that the consumer cannot own or possess a service; and the fact that the provider of the service can establish control over how the service is used, adds to the risks of purchasing some services. Moreover, services cannot be returned for reimbursement if the customer is dissatisfied.

- Inseparability; Services are performed and consumed simultaneously. Unlike manufacturing businesses that can institute quality control systems during the production process, hotels generally lack this luxury. They cannot send back, rework or scrap a defective service. Hospitality services cannot be inventoried and sold at another time. Potential revenue resulting from unused capacity is lost forever.

- Face-to-face interaction; Despite attempts to bring a ‘production line approach’ to some service situations, hospitality services entail extensive and intensive guest-employee contact and interaction. Since customer satisfaction is derived from performance rather than possession, the customer is buying the capabilities of the provider of the service. Service businesses, therefore, are evaluated on the basis of their personnel, their skills, knowledge and their ability to make the guest feel wanted, important, safe, comfortable, reassured (the intangibles of service).

- Heterogenity; Many service interactions are routine and can be standardized. With respect to these interactions customers will base their evaluation on the degree to which these services are consistent and simple. Control of these processes can be easily managed by hotels. However, not all service interactions are routine and require a deviation from the norm. Customer evaluation then is based on the ability of the employee to perform a service or correct a problem in a way which is most satisfactory as far as the guest is concerned.

In sum, services can be best explained as an ‘experience’ that is unique to the person (customer). This experience is made up of an intangible core of characteristics coupled with a variety of intangible and tangible facilitating mechanisms. For example a hotel experience may consist of and be affected by the following:

- Reception - Queuing time, handling of reservation, registration, credit check, processing time.

- Rooming - Luggage handling, provision of information.

- Stay in - Provision of furnishings, layout, room size, decor, colour, smell, comfort of bed, cleanliness, upkeep, TV reception, wake-up calls, quietness, ability to get a good night’s rest, safety, security, temperature.

- Check-out - Queuing time, processing time, payment of bill.

These are just some of the variables. Other factors may include the following:

- Expectations - (Based upon past experience, word of mouth, advertising), brand name, symbolism, image and ability to serve needs of belonging, security, identification, recognition, status, comfort.

- Purpose of visit - Type of use, objectives, problems to be overcome, other activities to be pursued.

- Location - Accessibility, ingress and egress, safety and security of neighbourhood.

- Availability - Choice of room, activity.

- Facilities - Type and range of restaurants, and bars, meeting, shopping and recreational facilities.

- Food and beverage - Taste, aroma, presentation, temperature.

- Atmosphere - Projected image or impression, mood, sights and sounds, colour, furnishings, lighting, heating, ventilating, novelty.

- Clientele - Number and type of guests staying or patronizing the hotel, crowdedness, rowdiness.

- Service personnel - Attitude, skills, knowledge, friendliness, courtesy, recognition.

- Price - Pricing policies, range of prices, credit.

- Service delivery - Speed of service, type of service provided, accuracy, timing.

- Safety, security and sanitation - Alarm systems, fire policy, preventative maintenance, safety deposits, cleanliness, guarantees.

- Information - Signage, knowledge of places and activities within hotel and community, promotional material, guarantees.

The idea that the hospitality service audit is an independent review is of paramount importance. It means that the auditor is not the person responsible for the performance of the product/ service under review nor is the auditor the immediate supervisor of that person. The auditor is an examiner or appraiser not a policeman of that person or enforcer.

The audit must be conducted from the customer’s point of view not how management sees, measures or evaluates quality. That is not to say there cannot be a degree of consensus, but that the standards set by management may not be the same as for the guest - they could be either too high or too low.

It is necessary for the auditor to become knowledgeable about the hospitality service offerings as well as those of competitors so that all dimensions of service can be identified and appropriate rating systems developed.

Developing a guest’s mentality. For the auditor to place himself within a particular role, he should become familiar with the typical events and activities that a typical guest might pursue prior to, during and after the stay. For the hotel audits, the auditor may have to talk to others who might have visited the hotel and/or the destination; read travel books or articles about the destination and the hotel; discuss the stay with a travel agent; make the necessary arrangements - reservations etc.

Auditors are required to experience the dimensions of hospitality service as would a typical customer and evaluate them at the same time. Therefore, sufficient time must be allotted to do both. This means that the auditor must have time to ‘live the experience’ as a guest.

The auditor must appear to be a typical guest in dress, manner and behaviour. In terms of being an observer the auditor is expected to be curious. This requires the auditor to play down or not to rely solely on an ‘insider-expert’ role. By becoming an ‘acceptable incompetent’ or by adopting a role of a student or one who is to be taught, the auditor improves his effectiveness.

The auditor who is familiar with the type of business and with the field of quality auditing may be better equipped to observe and notice deficiencies and may be better able to communicate his thoughts to management in a systematic and objective manner and in a language they understand.

The most effective audit procedures require auditors to conduct evaluations by actually observing how guests interact with the hotel’s systems and participate in various service-related activities or performances.

This qualitative kind of information gathered in this manner is unavoidably subjective in that it involves feelings and impressions rather than numbers.

While the actual scoring or determination of deficiency is not made until the audit is completed, the auditor prepares himself by making mental notes and taking jotted notes during the actual time in which he participates in and observes the provision of service (participant observations).

The underlying rule is to minimize the time between observation and notewriting. Of course, this takes considerable personal discipline and time.

The auditor’s task is really to ask ‘To what degree are guests satisfied with the dimensions of service?’

The auditor is free, indeed expected, to carry on conversations with people in the setting (fellow guests and even employees). Because conversation can be very informational and observational in nature, questions asked and answered stimulate new ways of looking and listening, as well as new questions to ask. In this way the whole process of evaluation is enriched.

Even though the auditor is concerned with differences or variances there is the temptation to move on into questions of how frequently something happens or with what that frequency is correlated. Auditors, as participant-observers, who spend insufficient time in the setting are not organized to deal with these quantitative questions.

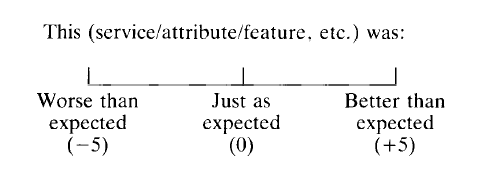

A meaningful approach from a guest’s standpoint is a better-and- worse-than-expected scale.