Research: Perspectives on gift exchange and hospitable behaviour

Paper (1982) by: John Burgess. Source: https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4319(82)90023-8.

I have read the paper so you don't have to. The 5 biggest lessons that teach you about the essence of hospitality, tourism and leisure management.

Gift exchange is a rich and revealing avenue of investigation, and an interesting perspective on general social behaviour and hospitality in particular.

Gifts of welcome are a common feature in the reception of strangers, which have developed with counter gifts into a system of barter (ancient Aztecs and British Guyana tribes).

Primarily, gift exchange has as its central philosophy the initiation, expression and renewal of social relationships, and benefit to the parties is social, moral and symbolic rather than economic.

Inseparable in each activity is the obligation to repay, and, through reciprocity inbalances, stem a source of power and status. The social exchange of gifts and hospitality serve to build up social networks and maintain social stability.

Firth (1973) comments that the essence of symbolism lies in the recognition of the one thing as standing for another to the extent that it appears capable of generating and receiving effects, often highly emotional, otherwise reserved for the object to which it refers.

As the gift imposes identities upon the giver and recipient, so too does the character of the hospitality offered (whether in a luxury hotel, hamburger restaurant or private house).

A refusal of a gift or act of hospitality may be interpreted as a rejection of generosity, friendship and social relationships.

Care must be taken by the recipient to return the hospitality or gift within the band of tolerance which ensures the continuing social relationship, whilst avoiding the return completely or with an exact equivalent gift or one totally out of balance with the gift originally received.

The special magic of the first gift is often never equalled as it is seen to be free of the weight of moral obligation inherent in subsequent exchanges.

At the extremes of experience, the customs of one society may appear incredible, bizarre or immoral to those in another geographic and cultural situation.

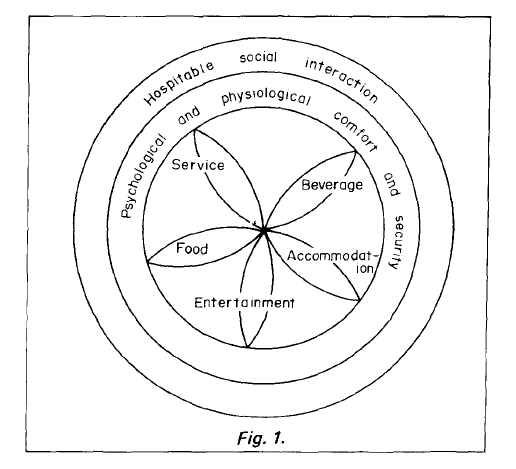

The hospitality elements may be represented conceptually as a package (Fig. 1).

The outer, primary interacting element is that of the social relationship fostered by the warm, friendly, welcoming, courteous, open, generous behaviour of the host, creating the hospitable social environment. This supports and promotes the positive feeling of security and comfort created by the physical structure, design, decor and location of the facility. Finally, the provision of accommodation facilities to sleep, eat, relax and wash, together with the supply of food, beverage, service and entertainment.

As the central aspect of hospitality and gift exchange involves the development of social relationships it is necessary to study the processes involved in social interaction at individual level. A person participating in a gift presentation or hospitality event makes personal sense of the definition of the situation by constructing a reality through anticipation of the encounter from cultural understanding and past experiences (Kelly, 1955). Roles emerge as a way of relating to others, behaviour patterns are defined and actual roles improvised on the basis of the imputed other role and understanding of their mutual construct systems.

'Role-taking' [is the notion] by which the individual attempts (despite difficulties and limitations) to see the world from the other's perspective and in understanding that position, adjust his social behaviour accordingly. From the interactionist's perspective it is the foundation to establishing meaningful and successful relationships in social interaction and facilitates control and power in human relationships. In hospitality for example, where the creation of relationships is central to the purpose of the event or product offering, it is the role-taking of the guest which, as Charon (1979) emphasises, is of paramount importance.

Within the formative stages of an interaction the negotiation of social identities is of prime concern to establish agreement on broad outlines of who each party is in the interaction (McCall and Simmons, 1966). Through the presentation of self the actor not only declares his identity but altercasts the role for the other. In behaving as a host the actor casts the other in the role of guest, and likewise the presentation of the role of donor imposes on the other the role of recipient.

Everything that is done within the context of the hospitality act, and gift exchange, either in full or part, affects others and consequently communicates to others.

In commercial hospitality organisations, the actors rarely identify themselves as host and guest, but rather as staff and customers. The latter tend to become labelled at '425', 'British Plastics Ltd.' (according to hotel room number or company affiliation), or as punters. Likewise, hosts become food handlers, room clerks, or management. Though role reciprocity, they are both defined and subsequently behave as 'room 425' and 'management'. The claims and obligations between host/guest roles and staff/customer roles are different in content and sentiment.

In public as well as in private hospitality, the interpersonal relations between actors are a crucial factor determining the nature and outcome of the event.

The continuum of social distance is an indication of psychological closeness of two people (e.g. host and guest, donor and recipient) established upon the individual's personification of the other, which ranges from close intimate liaison, to very formal behaviour involving the minimum of interpersonal relations. [...] Here devices such as etiquette, rules of social and professional behaviour assist in creating social distance. The development of interpersonal relations is largely

dependent upon cultural and personality differences and the period of association.

Herein lies the paradox for commercial hospitality. This has tended to ritualise, formalise and neutralise the 'service ideal' by distancing hospitality, reducing interpersonal involvement and variously creating a subordinate staff status. Organisations which now wish to reflect current society expectations and introduce hospitality must tackle established cultural traditions.

The increasing use of staff name badges for example allows guests to engage staff at a closer social distance and rather than address an individual as 'porter' or 'waiter' (and perhaps encounter just that) have the facility to use 'Harry' or 'Miss Jones' and hopefully will thereby experience a closer interpersonal interaction. Similarly, for management who over recent years have become increasingly caught up with behind the scenes administrative functions, would be advised to perform

a more 'public host role' thus imposing a defined 'guest role' upon their clients. The assertion that 'the gift without the giver is bare' becomes pertinently re-coined today to read 'hospitality without the host is bare'.