Research: Service clues and customer assessment of the service experience

Paper (2006) by: Leonard L. Berry, Eileen A. Wall and Lewis P. Carbone. Source: https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2006.20591004.

I have read the paper so you don't have to. The 5 biggest lessons that teach you about the essence of hospitality, tourism and leisure management.

Customers see more and process more information than managers and service providers often realize. Customers frequently behave like detectives in the way they process and organize “clues” embedded in the service experience into a set of feelings.

Services are performances rather than objects. [...] The primary source of value creation for a service is performance for the purchaser. When customers buy services, they do not assume ownership or possession. They buy airline transportation, car rental, hotel, restaurant, and other services during a trip, but they bring little if anything tangible home with them as a result of these purchases.

In general, services present many more customer “touch points,” or discrete sub-experiences, than do manufactured goods. [...] Purchasers of services often visit the place where services are created and interact with the people creating the service, such as hair stylists, salespeople, and dentists.

A reality of services consumption is that customers buy the service before they fully experience it.

If the customer can see, hear, taste, or smell it, it is a clue.

In interacting with organizations, customers consciously and unconsciously filter experience clues and organize them into a set of impressions, some more rational or calculative and others more emotional.

Specific clues carry messages; the clues and messages converge to create the customer’s total service experience. Clues tell a service story in the most powerful of ways, and it is better to tell a consistent, cohesive, compelling story than an inconsistent, disjointed, uninteresting one.

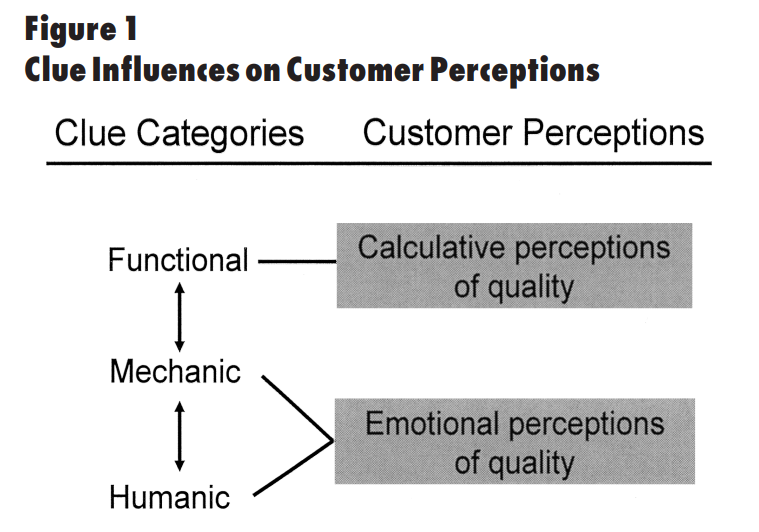

Clues generally fall into three main categories (Haeckel et al. 2003): functional clues, mechanic clues, and humanic clues.

- Functional clues; Functional clues are the “what” of the service experience, revealing the reliability and competence of the service. Anything that indicates or suggests the technical quality of the service—its presence or absence—is a functional clue.

- Mechanic clues; Mechanic clues come from actual objects or environments and include sights, smells, sounds, tastes, and textures. Whereas functional clues concern the reliability of the service, mechanic clues concern the sensory presentation of the service.

- Humanic clues; Humanic clues emerge from the behavior and appearance of service providers— choice of words, tone of voice, level of enthusiasm, body language, neatness, and appropriate dress.

Functional, mechanic, and humanic clues play specific roles in creating the customer’s service experience. Functional clues primarily influence customers’ cognitive or calculative perceptions of service quality. Mechanic and humanic clues primarily influence customers’ emotional or affective perceptions.

Managers should recognize that technical competence in service performance is not enough if they aspire to build a reputation for superior service and build preference for their company. How the service is performed is important to customers too, because it influences the emotional perceptions of quality.

Customer perception of employee effort in delivering a service has an especially strong impact on service satisfaction and loyalty (Keaveney 1995; Mohr & Bitner 1995).

Functional clues support the core of any service because they address the problem that brings the customer to the market.

Knowing what functional clues will comprise the evaluation of the core service and managing them well is fundamental to meeting customers’ service expectations.

Mechanic clues come from inanimate objects and offer a physical representation of the intangible service. The customer who is considering retaining an attorney cannot directly see the attorney’s competence but can see mechanic clues such as diplomas and awards hanging on the office wall.

Part of the first impressions role that mechanic clues play is their influence on customers’ service expectations. Customers’ perceptions of service quality are subjective evaluations of a service experience compared to their expectations for the service. Along with price level, mechanic clues function as implicit service promises suggesting to customers what the service should be like.

Mechanic clues directly influence customers’ service perceptions because these clues are part of the experience. Uncomfortable seats in a movie theater, offensive signs in a retail store (e.g., “break it and you’ve bought it”), and tables too close together in a restaurant directly detract from the experience. Mechanic clues are especially important for services in which customers experience the facilities for an extended time period, such as airplanes, hotels, and hospitals. Mechanic clues are quite salient to value creation in these types of services.

Humanic clues created by employees are most salient for labor-intensive, interactive services. The more important, personal, and enduring the customer-provider interaction, the more pronounced and emotional humanic effects are likely to be. Human interaction in the service experience offers the chance to cultivate emotional connectivity that can extend respect and esteem to customers and, in so doing, exceed their expectations, strengthen their trust, and deepen their loyalty.

As discussed, functional clues are usually most important in meeting customers’ service expectations because functionality offers the core solution customers buy. Conversely, humanic clues are typically most important in exceeding customers’ expectations for labor-intensive, interactive services, because treatment of the customer is central to these service experiences and superb treatment can evoke pleasant surprise.

Exceeding customers’ expectations, by definition, requires the element of pleasant surprise and the best opportunity for surprising customers is when service providers and customers interact (Berry et al. 1994).

Human interaction affords the best opportunity to demonstrate to customers a commitment to serving.

Excellent mechanic clues rarely can overcome poor humanic clues. The clues that people emit have greater impact on how customers feel about themselves and therefore have a definitive impact on how they feel about an experience.

Fundamental to any effort is understanding the experience from the customer’s perspective—that is, seeing what the customer sees, hearing what the customer hears, touching what the customer touches, smelling what the customer smells, tasting what the customer tastes and, above all, feeling what the customer feels. Organizations need to work to become more clue conscious and understand the level of subtle details that are processed in customers’ conscious and unconscious thoughts impacting how they feel in an experience. Understanding what customers sense in an experience either by its presence or absence is foundational.

Beyond understanding what customers sense from the existing experience and the feelings and stories that experience creates, the organization must also invest in learning what customers want to feel in the experience, what will engage them cognitively and emotionally in a manner that creates strong preference and loyalty.

The results of an experience audit and consideration of a firm’s overall market strategy form the basis for the creation of an “experience motif.” The experience motif is ideally a three-word expression of what customers desire feeling in an experience. The use of three words as opposed to more words or a sentence is to keep the expression simple and focused so that it can be an effective tool to use in the assessment, design, development, and management of experience clues.

Although some organizations have had success structuring a “customer experience office” or appointing a “chief experience officer,” others have been less successful. [...] Genuine commitment at the top of the organization is essential because customer experience management is cultural and not just a function of infrastructure and research.

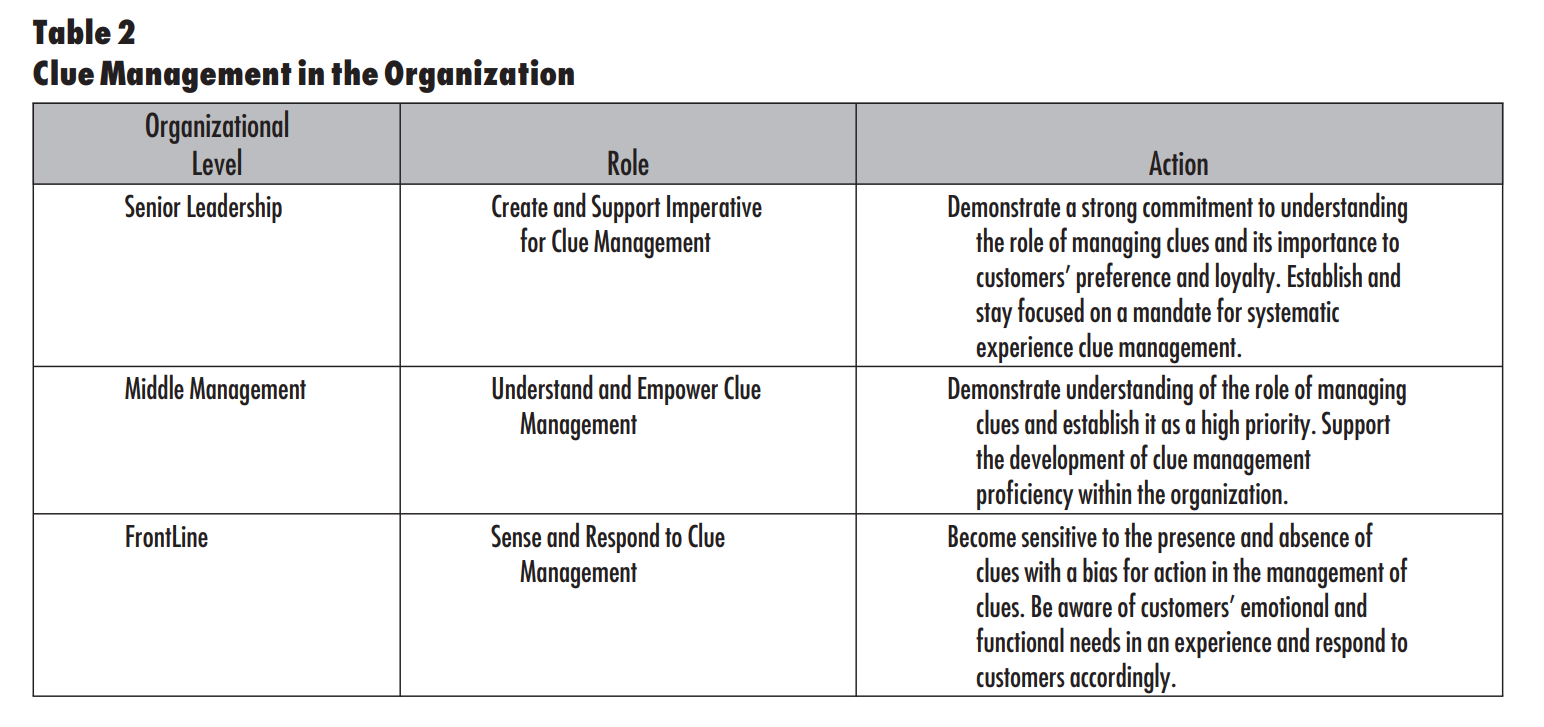

All levels of the organization play key roles in extracting the most value from managing service experience clues.

Whether managers put it all together— or don’t— customers do. They work out the “clue math.” They add up the clues and compute intricate conscious and unconscious calculations that influence their purchase decisions and shape their assessment of the service’s quality. Service experience clues and the value customers associate with the experience can lead them to loyalty and passionate advocacy— or the opposite.