Research: What is hospitality?

Paper (1995) by: Carol A. King. Source: https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4319(95)00045-3.

I have read the paper so you don't have to. The 5 biggest lessons that teach you about the essence of hospitality, tourism and leisure management.

Although the words hospital and hospitality have the same root, some hospitals have been seen as not very hospitable places. During the 1980s, when hospitals and other types of health care organizations began to compete for patients, being hospitable was seen as offering a competitive advantage (Super, 1986).

In order to improve patient satisfaction and retention, some hospitals instituted guest relations programs, in imitation of companies such as Marriott and Disney (Zemke, 1987; Betts & Baum, 1992). Many of these programs failed to achieve results, and by the late 198Os, guest relations programs were labelled a fad (Bennett & Tibbits, 1989; Ummel, 1991). One reason for the failure was a narrow focus on training front line employees to be courteous to patients, or improving their interpersonal communications and complaint handling skills (Peterson, 1988).

Bennett and Tibbits were critical of guest relations programs, which were often purchased as a package from an outside source. Such programs were ineffective because they were merely imposed on top of the organization, rather than being an integral part of its mission and culture.

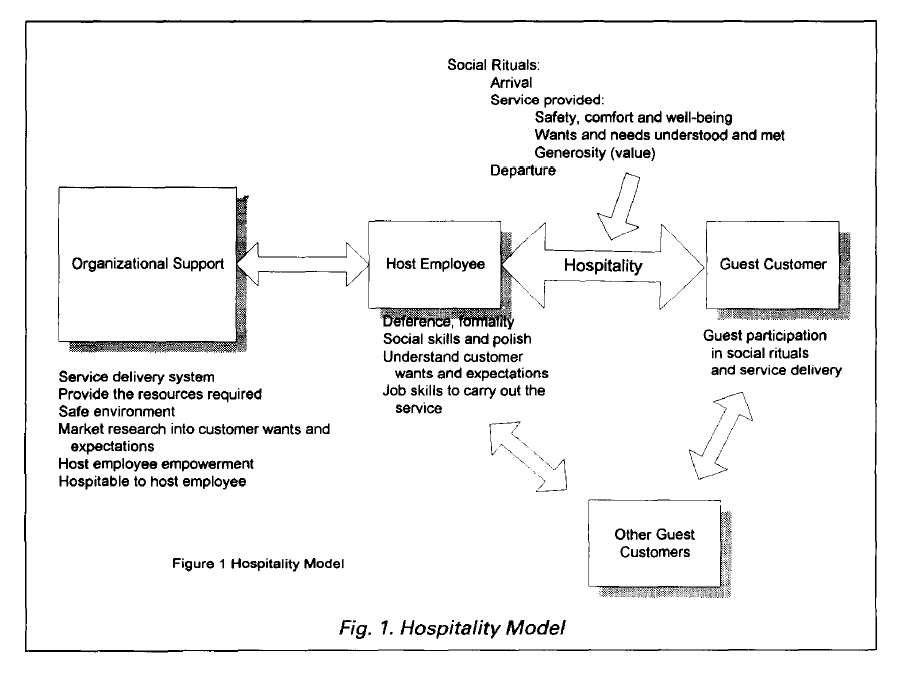

Commercial hospitality has several key elements that must be included in a model of hospitality that has application beyond the hospitality industry (Fig. 1).

The idea of hospitality dates from ancient times (Durant, 1935,1939; Gray and Liguori, 1980; Heal, 1990; Smith, 1974; White, 1970). Travel was extremely dangerous, and to be without shelter for the night could mean death by exposure to the elements or wild animals, or robbery and murder at the hands of highwaymen. Many societies developed an ethic of hospitality to allow a degree of safety for travelers, without which there could be no travel or trade. In such societies, a host was bound by a code of hospitality to protect his guest from robbery or bodily harm. At the same time, the guest was under an obligation not to harm to the host.

White (1970) observed that the harder the physical conditions, the greater the obligation of hospitality. He gave two examples: Arab hospitality in the desert, where to hesitate in setting food before a stranger would be shameful (p. 9), and Arctic hospitality of the Eskimos, who place their wives at the disposal of their guests (p. 10).

The existence of rituals implies the existence of rules for conducting rituals. Visser (1991) observed that table manners are a system of civilised taboos that work to reduce tension and protect guest and host from one another in a situation fraught with potential danger (p. 92). The laws of hospitality prevent host and guest from attacking each other with knives at the table or when the guest is defenseless.

The ancients attached meaning to the arrival of a traveler at the gate and passage over the threshold. Rituals of arrival incorporate the stranger and the strengths he brings into the group harmoniously. They define membership in the group and relative status of the members.

The architecture of walls, gates, corridors and doors is a part of the arrival ritual (Heal, 1990; Leed, 1991). Walls define the ‘within’ and the ‘without’, marking the boundaries of the group, and boundaries imply an ‘us’ and a ‘them’. Arrival areas or public spaces may be designed to make an impression on the visitor, a practice that is evident in modern society in hotel lobbies, which are usually much grander than the guest rooms upstairs. Rituals associated with the visitor’s arrival at the gates and movement through them marked the shift of status from an outsider to insider, one of ‘us’. These rituals also recognized the visitor’s status relative to the host. Higher ranking guests were admitted to private inner areas not accessible to non-ranking visitors.

A difference in demeanor between American and European innkeepers and their

employees has been described in various 19th century texts (White, 1970). The Americans rejected a servant-master relationship with their guests. Whyte (1948) noted in the 20th century that European waiters were more accustomed to social class differences and thus had fewer problems with customers than American waiters.

Judith Martin (1985), in a lecture at Harvard University, * quoted Alexis de Tocqueville on the impersonal manner of the Americans,

“An expression of the mutual recognition that any moment, the servant may become a master . . . Neither of them is by nature inferior to the other; they only become so for a time by agreement. . . beyond it, they are two citizens-two men” (p. 57).

The commercial guest-host relationship is not symmetrical, as Shamir (1978) pointed out. It is the host’s role to provide and the guest’s role, which is voluntary, is to receive. The relationship is reciprocal only in that the guest is obliged to pay for the service received and not cause harm or undue disruption to the business, its employees or other guests. The hotel’s mission is to provide relatively simple maintenance services to guests, In competition with other hotels. The innkeeper does not have the advantage of superior specialized knowledge over the guest, as does a lawyer or physician. This, and the existence of competition, gives a high degree of control to the guest. Additionally, the service interaction is often between customers and lower status employees, giving the customer direct control over part of the staff’s behavior. This control is further enhanced in some departments by tipping.

The service employee has a struggle between catering to the guest and maintaining control over the service transaction to perform the required tasks effectively. At the same time, the employee must satisfy the company’s standards and requirements, and still keep his or her own emotional equilibrium and self esteem.

Friendliness in the host-guest relationship is not always appreciated. [...] Friendly relationships lack formality. Visser (1991) discussed formality as social differentiation, placing distance between someone who is outside the group (the servant), and the in-group of guests or diners. Formality may be a way of managing the host-guest relationship to reduce role stress.

From this overview of the history and sociology of hospitality, we can describe hospitality in general as having four attributes:

- First, hospitality is a relationship between individuals, who take the roles of host and guest. The host provides generously for the well-being, comfort and entertainment of the guest.

- Second, this relationship may be commercial or private (social). In the commercial relationship, the guest’s only obligation is to pay and to behave reasonably. The guest holds the power to go elsewhere for service if the hospitality provided is not satisfactory. Private or social hospitality assumes an equality of power, and the guest has a social obligation to contribute to the relationship by being good company, and to reciprocate to the host in some way.

- Third, the keys to successful hospitality in both the commercial and private spheres include having knowledge of what would invoke great pleasure in the guest, and delivering it flawlessly and generously. Inherent in the hospitality, but perhaps not always evident is the concern for security for both the guest’s person and property.

- Fourth, hospitality is a process that includes arrival, which involves greeting and making the guest feel welcome, providing comfort and the fulfillment of the guest’s wishes, and departure which includes thanking and invitation to return. At each step of the process, these courtesies, or social rituals are enacted and define the status of the guest and the nature of the guest/host relationship.